|

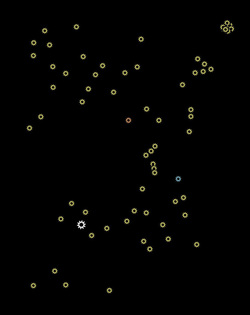

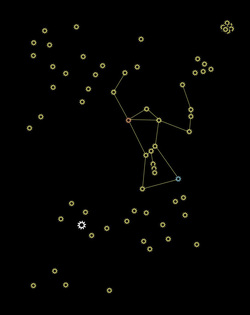

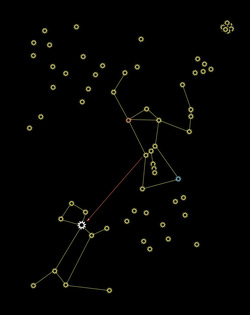

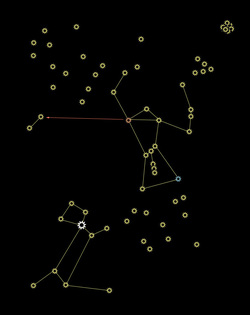

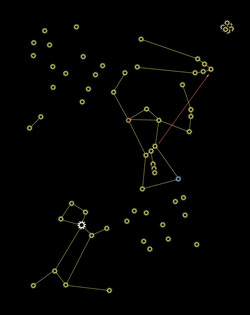

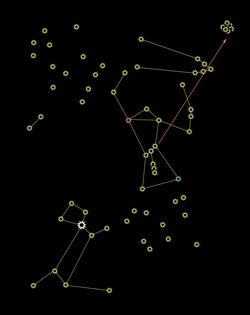

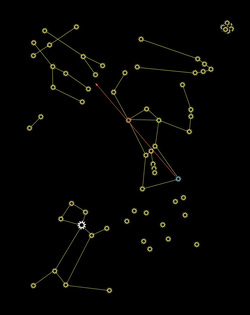

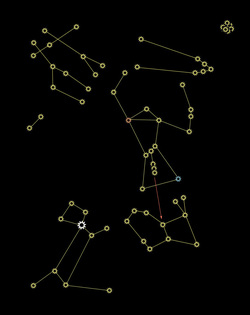

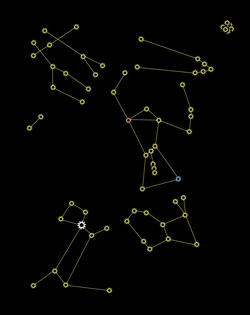

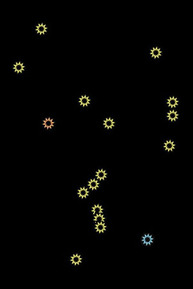

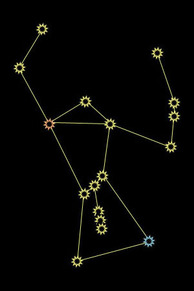

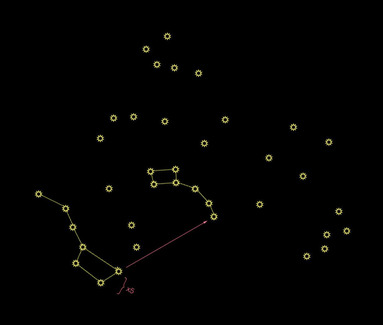

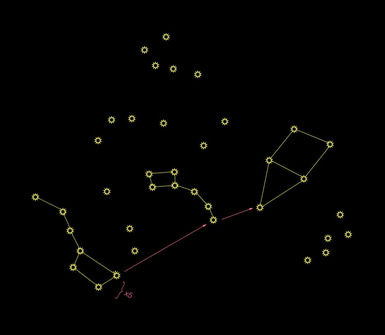

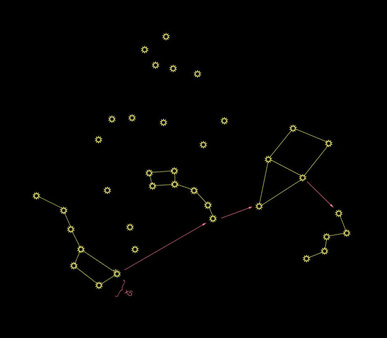

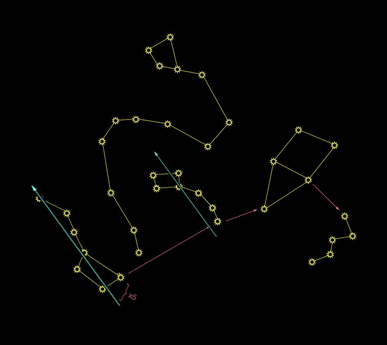

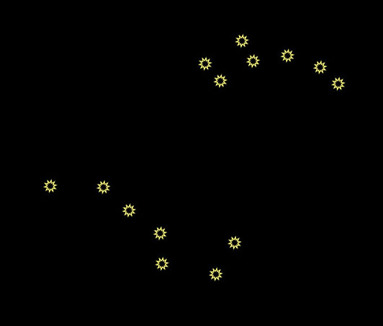

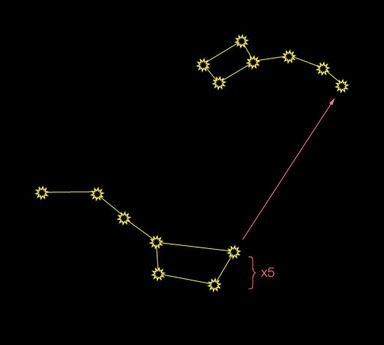

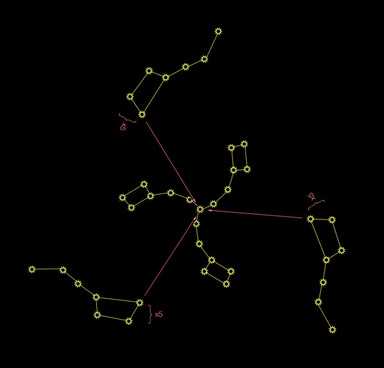

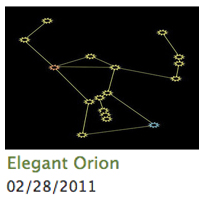

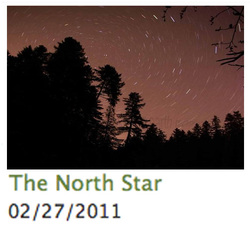

_Now Available in E-Book and Paperback! If you haven't already, please start by reading Lesson 1: The North Star, Lesson 2: The Circumpolar Constellations, and Lesson 3: Elegant Orion before proceeding.  Review from previous lessons: The circumpolar constellations rotate in a tight circle around Polaris, the North Star. They are always above the horizon if you're in the northern hemisphere. Other constellations are farther away from the North Star, and rise and set like the sun. Different constellations will be visible during prime star-watching time (from early darkness to bedtime) at different times of the year. In the last lesson, we became familiar with Orion. Here he is with some of his closest neighbors. Can you spot him? Look for his belt, and then confirm by finding Rigel and Betelgeuse.  Orion, the Hunter: The stars in Orion can be used to find other nearby constellations, much the same way that the pointer stars in the Big Dipper directed us so effectively toward Polaris. We can use his belt, his shoulders, his dagger, and Rigel and Betelgeuse to find Canis Major, Canis Minor, Taurus, The Pleiades, Gemini, and Lepus. That big white star you see is the only magnitude difference I'll show, but only because it is the single brightest star.  Canis Major, the Big Dog: Follow Orion's belt down to the left. You'll come to a bright star, Sirius (it's a seriously bright star). It's so bright, in fact, that it's the brightest star you can see from Earth, other than our sun. That makes it the brightest star you can see from Earth at night. Sirius is the diamond on the collar of the big dog. It is sometimes called the "dog star." Ursa Major (the Big Dipper) is the Great Bear, and Ursa Minor (the Little Dipper) is the Little Bear. It probably follows, then, that if there is a BIG dog, there should probably be a LITTLE dog, too (the same logic follows for anything with Northern/Borealis or Southern/Australis in the title, as well).  Canis Minor, the Little Dog: Follow Orion's shoulders sideways to the left, and you'll come to Canis Minor, or the Little Dog. The Little Dog is just two stars, so it looks more like a hot dog. The brighter of those two stars is called Procyon (PRO-see-ahn), which is Greek for "before the dog." This is in reference to how the stars rise. You will always see Procyon rise above the horizon before you see the "dog star," Sirius. Canis Minor is one of the 88 modern constellations, but was not recognized by the ancient Greeks. According to the Greeks, Orion had only one dog. Maybe she had puppies.  Taurus, the Bull: Follow Orion's belt up to the right, and you'll come to the nose of Taurus, the Bull. Taurus's face is a little V shape, and he has long horns reaching far behind his head. Taurus has a reddish star, Aldebaran (ahl-DEH-buh-rahn). It's the star closest to the top of Orion's shield (the star that marks the top of the bull's face and the bottom of his horn).  The Pleiades, or the Seven Sisters: Continue past Taurus until you reach a little blurry patch in the sky. That little blurry patch is a cluster of stars known as the Pleiades, or the Seven Sisters. In Japan, the star cluster is known as Subaru (check the car company logo next time you find yourself near a Subaru). The cluster is made up of hundreds of stars, currently passing through a dust cloud (hence the blurriness). Most constellations appear the way they do from Earth because of our perspective; if you went to another solar system, they would look completely different. The stars in The Pleiades, on the other hand, are physically near each other in space, so they will look like a cluster from any vantage point.  Gemini, the Twins: Draw a line from Rigel to Betelgeuse, and then continue up to Gemini. The stars that make up the heads of the twins are called Castor and Pollux. The head-stars are very bright, and will likely be one of the only recognizable parts of Gemini when you see it in the sky. Locate the twins carefully! The two head-stars look an awful lot like Canis Minor if you're only going for an approximation. Shoulders sideways gets you to the little dog, and the Rigel-Betelgeuse line gets you to the twins. Pollux has really long legs, and Castor has really short legs, so clearly they're fraternal twins.  Lepus, the Hare: Shhh! I'm hunting wabbits! Orion, the hunter, needs some prey, and his dogs like to chase things. Follow his dagger downward to find a rabbit, Lepus. It's easy to remember the name of this little guy, because rabbits leap-us. Never mind that this gigantic lagomorphic monstrosity could probably take out the Little Dog with one well-placed kick of his non-existent legs...  Now you know all of Orion's neighbors! If you go back to the last lesson, you can see Orion in the photograph, along with Canis Major (everything but the tip of his tail), Canis Minor, and you can even see Pollux's toes (he's the long-legged twin). Lepus is there, too, about to dive nose-first into the Pacific Ocean. You now have at your disposal two whole patches of sky, and 11 of the 88 constellations, or 12.5% (The Pleiades is considered part of Taurus in the count). That number becomes even more impressive when you think about all the southern hemisphere constellations you don't have to worry about unless you travel there. _Now Available in E-Book and Paperback! If you haven't already, please start by reading Lesson 1: The North Star and Lesson 2: The Circumpolar Constellations before proceeding. So, now you're familiar with the North Star, and all of its circumpolar friends. Other constellations are far enough away from Polaris to rise and set the same way the sun does. Star charts are arranged with times of night, hour by hour, and months of the year. That's all well and good for advanced stargazers, but that's a level of complexity unnecessary for the beginner. Let's simplify: You're most likely to be stargazing from sometime between when it gets dark enough to see all the stars until, let's say... 11:30 p.m., right? I call that "prime star-watching time." Because of the position of Earth as it orbits the sun every 365 days, different constellations will be overhead during prime star-watching time depending on the season. Constellations visible on a summer night will be "up" during the daytime in the winter, so you won't be able to see them. The Summer Triangle is a great example of an asterism you can see during the summer. I call those "summer constellations." We'll get to some of those later. For now, we're going to focus on one of my favorite fall/winter constellations, Orion. He'll be most visible during prime star-watching time from Octoberish through Februaryish. How to find Orion? Find that Big Dipper again. Now turn around, approximately 180°. You should be facing the correct general region of sky.  Here's my friend Orion, with just his stars. A well-known asterism (remember, that's a recognizable group of stars that aren't technically a constellation by themselves) in Orion is his belt. Those three diagonal close-together stars make up the belt, and those stars are the easiest way to find Orion in the sky. Orion has several interesting features. Notice that blue star down in the corner? That's actually a blue star. Blue stars are younger, smaller, and hotter than your average yellow star. This one is called Rigel (RYE-jell). Rigel is around 800 light years away, which means when you see that blue star, you're seeing the light that left Rigel 800 years ago. That sounds pretty far away, but in the grand scheme of the Universe, Rigel is pretty close to Earth.  Up and to the left (the shoulder opposite Rigel), there's a red star (not RED-red, just kind of pinkish-orange). Red stars are older, larger, and cooler than yellow stars. That one is called Betelgeuse (BAY-tell-jooz, or, as almost everyone says, beetle-juice). Betelgeuse is a red supergiant. It is almost 2000 times the radius of our sun, and could fit within it over 2,000,000,000,000,000 Earths. Betelgeuse is expected to become a supernova sometime in the next million years or so. Because of its distance from Earth, it's possible that it has already done so, but the light from such an event would take hundreds of years to reach us. The dagger hanging from Orion's belt contains a nebula. The middle "star" you see is a nebula made up of dust and gasses, which will eventually condense enough to form new stars. A birthplace for stars is visible from Earth with the naked eye!  Here is an actual photograph of Orion hanging out on the Oregon Coast. Can you find his belt? It's nearly horizontal in this shot. Now find Rigel (only very slightly blue in this photo), and Betelgeuse (definitely pinkish-orange) and the dagger hanging from the belt. Orion is a hunter. He holds his shield in the arm shown on the right hand side of the diagram above, and a club or sword in the arm with Betelgeuse as the shoulder. Orion hunts with his two dogs; we'll meet them in the next lesson, but they are visible in this photograph. After you become familiar with how to find them, come back to this lesson and check the photograph again.

In January of 2009, I took some friends to do touristy things in San Francisco. One of our stops just had to be the sea lions at Pier 39. Our timing couldn't have been worse. The sea lions had been there for 20 years, but just that winter, they decided to leave.

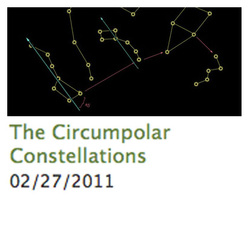

So we stood there, looking at the empty docks, waiting... This chap in his bright yellow boat out for a morning row was interesting enough, I guess. We did eventually get a small pile of sea lions, but it's just not the same as hundreds. The sea lions have since returned, so we'll just have to plan another trip. What I love most about this photo, is that this little jaunt around the harbor is probably this guy's daily routine. Some people go jogging, some people go have coffee in a little coffee shop while they read the morning paper. This guy takes his bright yellow boat out for a row. Maybe he's used to tooling around the massive marine mammals, but for the last little while, these docks have been unusually quiet for his morning row. _Now Available in E-Book and Paperback! If you haven't already, please start by reading Lesson 1: The North Star before proceeding. As we add more constellations to your repertoire, don't get discouraged if you can't remember all of them right away. Learning your way around the night sky takes patience. Take it one or two constellations at a time, and quiz yourself every time you're outside on a clear night.  The Circumpolar Constellations: The stars closest to Polaris (the North Star) will always share that region of sky. Since Polaris will never rise or set, those nearby stars will also be above the horizon most of the time. These are good constellations to become familiar with, because they are always "up" when you want to be stargazing. Quiz from the last lesson: Can you find the Big Dipper? Can you use the pointer stars to find Polaris? How about the Little Dipper?  The Big and Little Dippers: OK, you remember how to find these from last time. Here they are with some distractions. Three more circumpolar constellations are shown here. We'll go through them one at a time. Remember that the stars are not all the same level of brightness, but they're shown equally here for simplicity.  Cepheus, the King: If you use the pointer stars on the Big Dipper to find Polaris, and then keep going, you'll come to the tip of the crown of King Cepheus. The square is his head, and the triangle is his crown. He's upside-down here. Cepheus may be a bit tricky to find, as he is composed of mostly fainter stars. Look for him if you are somewhere without much light pollution and no full moon.  Cassiopeia, the Queen: There are two stars marking where Cepheus's crown meets his face. Cepheus always looks away from the little dipper and toward his wife, Queen Cassiopeia, so the star farther away from the Little Dipper is his eye. Follow Cepheus's gaze to Queen Cassiopeia. She's the Queen of M&Ms! OK, not really, but she looks like an "M" or a "W" in the sky. The shape represents her royal throne, in which she sits admiring herself all day.  Draco, the Dragon: If you create two roughly parallel lines out of the Big Dipper and the Little Dipper, you'll see a semi-straight line of stars in between. This is the end of the tail of Draco. Follow it up, and curve around the little dipper, then snake your way up again to find the wonky trapezoid that marks his head. I like to think of Draco as the type of dragon one would find in a Chinese New Year Parade: a head followed by a long, colorful tail. Bonus Nerdy Bits: The name "Draco" has become quite recognizable as of late, from J.K. Rowling's Harry Potter series. Rowling used many names from astronomy for her characters, including Sirius, Bellatrix, Pollux, Regulus, Arcturus, Alphard, Cassiopeia, Cygnus, Andromeda, Orion (OK, so it's mostly members of the Black family...) Now Available in E-Book and Paperback! This series of stargazing lessons will walk you through many of the constellations visible in the northern hemisphere. Once you have mastered these, you'll be ready to look at any star chart and learn the rest on your own. For simplicity, the stars in my diagrams are not shown with relative brightness taken into account. When you see the stars in the sky, some will be bright and clear, and some will be very faint. For best results, try to do your stargazing as far away from city lights as you can. Turn off porch lights and other night-vision-destroyers (or block them with your hand as you look at the sky). Choose moonless nights for stargazing. As it turns out, you have to start somewhere, so there's a prerequisite for this course: find the Big Dipper yourself. If you don't already know it when you see it in the sky, have someone point it out to you. If you're in the northern hemisphere, it should always be above the horizon (as long as you're not too close to tall buildings, tall mountains, or tall trees), and it serves as a good starting place to orient yourself each night. Become very familiar with the shape of the Big Dipper, and keep working at it until you can always find it, and you're 100% sure that's what you're looking at when you do find it. Once you can do that, you may proceed.  The Big Dipper: The Big Dipper is like a giant frying pan in the sky. Technically, it's not a constellation by itself; it's an "asterism." An asterism is simply a commonly recognizable pattern of stars (It's the lower one). The Big Dipper is part of the Great Bear, or Ursa Major. The rest of those stars are sort of below and to the right of the frying pan, but for our purposes, they're not important. You can use the Big Dipper to find other things in the sky, which is why it's such a good place to start.  The Little Dipper and North Star: The two stars on the front end of the frying pan part of the Big Dipper are called "pointer stars." They point to the North Star, or Polaris. If you take the distance between those stars and extend the line out 5 times that distance, you'll arrive at the North Star. The North Star is at the tip of the handle of the Little Dipper, or Ursa Minor. The North Star is bright, as are the two stars at the end of the pan of the Little Dipper. The rest are tricky to see unless it's really dark.  Why do we care about Polaris? The North Star, Polaris, is not a particularly bright star compared to many other stars. The reason we pay attention to it is because it never moves. It is located directly above the North Pole. As the Earth spins on its axis, the sky appears to rotate (the same way that if you look straight up at the ceiling in your living room while spinning around really fast, the room looks like it's spinning, but it's really you - the North Star is the spot on the ceiling right above you). This diagram shows how the Big Dipper and Little Dipper move throughout the course of the night (and day), but the one star at the tip of the handle of the Little Dipper, Polaris, remains in the same spot the whole time. Each night as you begin to stargaze, the stars will be in a slightly different location than the night before (unless you start precisely 4 minutes earlier each night, but pretty soon you'll run into daylight). Finding the Big Dipper, and using that to find the North Star, will help you find your way around the rest of the sky.  This photograph was taken using a tripod with a 15 minute exposure. During the time the shutter was open, the Earth rotated enough to see a difference in the position of the stars. Polaris appears as a single dot (right next to that tree, almost like it's being cradled in the branches), other stars close to Polaris advanced just a little bit, and stars farther away show a great deal of motion. Notice that some of the stars appear to be different colors than others. I'll point out notable blue and red stars along the way as we learn more constellations. This photograph is called "Continuing Mission," and is available for sale in many formats here. Bonus Nerdy Bits: The middle star in the handle of the Big Dipper is actually 2 stars (well, if you want to get really technical, it's 6 stars). The stars are named Alcor and Mizar, and are sometimes referred to as the "horse and rider." If you look really carefully and have near-normal eyesight, you can actually see two stars very close together. It also helps if it's (once again) a really dark, moonless night.

Murrietta365 hosts a "Straight Out Of the Camera" (SOOC) challenge each Sunday, which proved to be harder than expected. Turns out there aren't very many shots that I don't edit at least a little bit.

So, after some digging, I found this little gem. Not only is it SOOC, but it's film! Remember that stuff? I took this photo with my Pentax 35mm SLR (not digital). I couldn't see each shot as I took it. I had a limit of 24 shots. I had to wait a whole hour to know if I had gotten anything good. I absolutely love digital photography, because it allows me to learn from my mistakes in real time. However, I think every photographer should dust off the old 35mm every once in a while for a lesson in patience, and to learn to think through each shot and the camera settings that will make it a good one. You can't rely on the habit of taking 50 shots of one subject knowing that, statistically, one of them will end up coming out OK (well, you can, but it gets expensive pretty quick). On this particular day, it was windy, and there was a cat that kept getting in the way of things (he was having fun nuzzling the side of my lens right as I was about to release the shutter). Some other shots from that same roll (yes, an actual roll) of film are shown below:

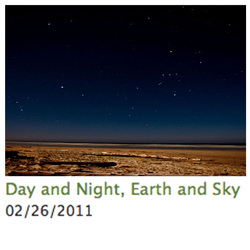

My favorite kind of sky: Dark, clear, and starry as all get out. Huge expanses of sky (for extra stars) are a plus, too. So while I love exciting topography and tall, tall trees, they just get in the way where stars are concerned.

I'm forever trying to get a good sky shot. This was a pretty good attempt. The full moon lit up the sand pretty well, but Orion and his mutts, Canis Major and Canis Minor are still clearly visible. This photograph is guest hosting over on SkyWatch this week!

This week's theme on Twisted Fate Photography is "park bench." I don't know if this technically counts as a park, but it's certainly a public space from which one might want to view something lovely while passing the time. I have taken several other fantastic shots from both this very spot and from the rocks just below:

Parks and natural spaces are lovely, and I love people-watching from benches, but I always wish I could be more invisible while I do so. Sometimes, spending time looking through a camera gives me an out, a way to ignore the people around me in a fashion that makes me look both busy and non-awkward. Sometimes I think I become more conspicuous when I'm using my camera.

It's these hangups I need to get over. My visit to Heceta Head to get these shots was nice because it was cold, and sunset, and very few people were around. I had some freedom to take the photos I wanted, and my only constraint was the length of time it took my fingers to go numb. I didn't sit in that park bench, but I did set my tripod up right next to it.

The theme of my Lazy 365 challenge is this: See a shot, then get out the camera and get that shot. Exactly that shot.

Found this while running some errands today. I have passed this sign before, and always liked the contrast of the red and white letters against the russet building and blue sky. Today, since I actually had to get out of my car and stand in the road to fulfill my challenge, I figured I should check out the deli, too; I've been looking for a good sandwich place.

Around the front of the building, there's a lovely awning with statues on either side of the doorway. I liked it right away. How had I never noticed the statues before? But then the sketchiness began... It was closed. Turns out, according to their hours, they're only open on Fridays and Saturdays, and for just a few hours each of those days. I tried looking in the window. It was unclear whether it was ever open. I don't know if I even want to go back to see if it perks up when it's in operation mode. Maybe operation mode isn't sandwiches at all...

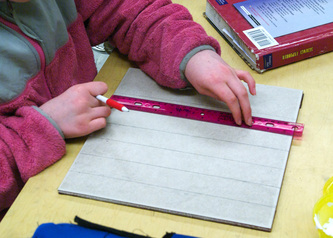

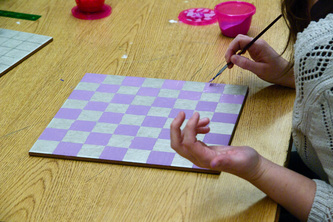

Conflict, 7th Grade:

Today the chess boards began to transform from nondescript beige tiles smudged with pencil lines to stunning fields of color and contrast. We added felt to the bottom so the tiles wouldn't scratch the tables, and when all coats are done, we'll add a clear layer of protective varnish to keep the paint from flaking off as future battles of kings and pawns are waged on the colorful surface.

All Culture and Conflict posts can be found under the topic heading: Diversion Audit.

|

Topics

All

Archives

May 2021

|

HOME |

PHOTOGRAPHY COLLECTIONS

|

© COPYRIGHT 2020. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed